r/Beekeeping Wiki

Varroa Destructor Mite

- Introduction

- Reproduction

- How they spread

- Mite bombs

- Pre-winter damage, leading to winter collapse

- Monitoring varroa infestation

- Available treatments

Introduction

Varroa Destructor Mite (VDM, or just Varroa) are a parasitic mite that migrated from Asia to the west in some time around 1980-1992. Since it’s arrival, the beekeeping landscape has changed substantially. Varroa mites are external parasites that feed on adult and developing bees. The mites are tiny, reddish-brown, and can be challenging to spot without close observation. Some users in our subreddit know what that world looked like from working with their family in the beekeeping businesses.

VDM causes untold colony losses every year. The mode by which this happens varies season by season, but generally speaking varroa does two things:

- Weakens the health of each individual bee being raised, thus weeakning the colony as a whole

- Directly infects individual bees with disease, thus weakning the colony as a a whole.

Varroa aren’t usually the direct cause of death for a colony, but are the root cause of the collapse. Similar to how a human subsisting solely on McDonalds and Dunkin’ might have heart attack. The direct cause of death is the heart attack, but the root cause is excessive fast food.

Treatments are available for Varroa. Think of it like treating a cat for fleas - the treatment does have an affect on the cat to some extent. In fact most pesticides are insanely toxic to cats, they can just handle it because they have livers and kidneys. Likewise, all treatments come at a cost to the colony, but do help with varroa loads more than they injur the colony as a whole. Take for example formic - that can push off brooding, cause supercedures, etc. It’s pretty potent stuff, but it’s for the greater good. Without treatments, almost all colonies eventually collapse.

The below pictures will give you an idea of the size of a varroa mite.

Image: Mite on the back of drone. Drone was excised from the comb for the purposes of the photo.

Image: Mite on the back of drone. Drone was excised from the comb for the purposes of the photo.

Image: Mite on thumb nail, so that you can see just how small they are. This is an adult female varroa mite.

Image: Mite on thumb nail, so that you can see just how small they are. This is an adult female varroa mite.

Phoresis

It’s worth noting at this stage what “phoretic” means. Phoretic mites are mites that are emerged from cappings and running around the hives. They are more often than not being carried around on a bee, not by the bee’s choice.

During the phoretic stage of a mite’s life, they are exceptionally vulnerable to treatments. Read the Treatments section for more information on this.

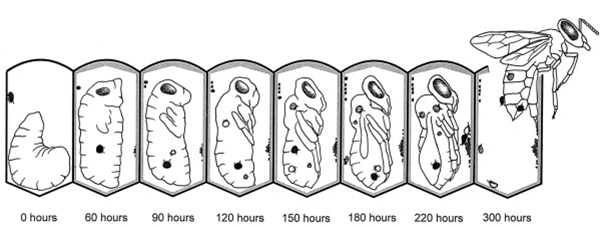

Reproductive Cycle

After emergence from a cell, varroa mate (depending on their sex) take 5-7 days to become sexually mature. Once they do, they find a nice looking cell that is just ready to be capped, and drop off of a bee into the cell.

The cell is then capped.

During this period, where the mite hides under the cappings of the cell, brother and sister varroa mate on a bed of waste. Their offspring feed on the larval bee during development. At this phase, multiple varroa will be feeding on the larval bee. Varroa prefer to mate on drone brood, as they can stay protected for longer and produce more offspring than on workers.

Once the bee has pupated and emerges, so too do the varroa.

Adult mites that have already mated will stay phoretic – clinging to an adult bee to be moved elsewhere within the hive or to another hive through drift – for 4-7 days and then go and mate again for another cycle. They can do this 3-4 times before being spent. Read from the top of the top of this section to find out what happens to their young :)

Key things to remember

- Adult varroa stay phoretic after each mating cycle for 4 days

- Young varroa stay phoretic for 5-7 days

- They prefer drone brood

How Varroa Spreads

Robbing: When a colony dies off it leaves behind its entire population of very patient mites, as they are robbed dry, robbing bees take back more than just honey. That’s why these colonies are known as “mite bombs”.

Drift: When bees (particularly drones) drift between colonies, they take more than just sperm with them. They also carry varroa.

Both of these things cannot be avoided or controlled. As such, varroa are largely unavoidable.

The Damage Varroa Do

Deformed wing virus is seen as an indicator of high varroa loads. However this diseases existed long before varroa. Previously, they were spread by trophallaxis, that is to say “spit swapping” of workers as they exchange food and pheromones around the hive.

With the introduction of varroa, diseases have a much more simple vector - direct injection. As the varroa feeds on the larva, they also “inject” the diseases straight into it. The larva have no defense against this and as such, high loads of varroa are usually indicated by high loads of disease, including stress disaeses.

However, this isn’t to say that singular findings of DWV (or other diseases) are indicative of high loads of varroa. As stated, these diseases existed long before varroa. They are endemic. If you find one or two bees with DWV, don’t panic. Just do a wash if you feel that it’s necessary and treat as necessary.

If your colony is suffering from a “stress disease” such as EFB or sacbrood, it’s a safe bet to wash a sample of bees (if they have the numbers) to ensure that varroa aren’t contributing to colony stress.

Pre-winter Damage

The real damage that varroa do largely goes unseen.

During summer, a large amount of varroa will be mating in drone cells, and the amount of worker brood will be huge compared to pre-winter. However, when autumn hits the bees will start brooding up winter bees, and remove drones and existing drone brood from the hive. This usually happens at around the equinox, though this date will fluctuate depending on where you live and the weather conditions.

When the bees remove drone brood from the hive, existing adult mites will look for somewhere else to mate. With no drone brood left, and a reduction in the amount of worker brood. This causes the number of adult mites per worker cell to jump by orders of magnitude.

The average summer bee lives for around 4-6 weeks. The average winter bee lives for around 4-6 months.

When the varroa numbers jump up so high on bees that need to have tip top health to survive that long, this spells on one thing: winter collapse. This will happen quickly, and without warning. One day you can tap on the hive and hear a loud hum of bees keeping the colony warm. The next day, nothing. Once the colony gets small enough that it can no longer keep itself warm, they will quickly succumb to the cold. A collapse of this nature is usually blamed on moisture, cold, or isolation starvation - all of which are indeed the immediate cause of the collapse, but not the root cause. Remember: varroa are like the McDonalds and Dunkin’ of a heart attack related death; the heart attack is the immediate cause, fast food is the root cause. You can read more about this on the Why Are My Beeds Dead page.

As such, treating for varroa pre-winter before they have a chance to damage winter bees is usually not optional. The ideal treatment plan will treat over the drone eviction period; or shortly before, covering a full drone brood cycle. Treatment options depend a lot on your climate, but local beekeepers will usually have a preference.

During the summer months, collapse due to varroa pressure is possible, and is referred to as “parasitic mite syndrome”. It can often look like other diseases, and is covered on our diseases section of the wiki.

Let us just make two things clear: The vast majority of winter collapses are due to unmanaged varroa, and varroa go unseen unless you go looking for them… and no we don’t mean with your eyes.