r/Beekeeping Wiki

Small hive beetles

The Small Hive Beetle (Aethina tumida)

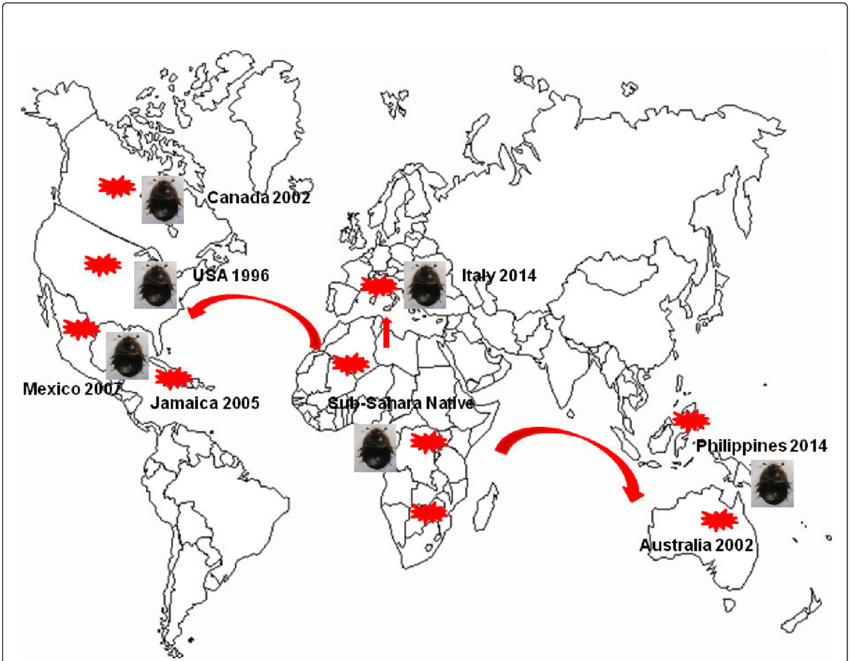

Small hive beetles (Aethina tumida) are a serious pest of honey bee colonies, capable of causing significant damage in a short period of time. Native to sub-Saharan Africa, they have now spread to many parts of the world, including the all of the United States except Alaska; Canada; Australia; Philippines; and Italy. Small hive beetles eat everything (pollen, brood, honey, dead adult bees and combs) in the colony, causing honey to ferment in the process. Fermented honey usually runs out of the comb, creating a mess within the hives or honey house. Although weak colonies are more prone to SHB invasion, strong colonies can also be overwhelmed.

SHB are small, dark-colored beetles, measuring approximately 5-7 mm in length. They possess a compact, oval-shaped body with a pair of clubbed antennae and a distinct notch on the posterior margin of their elytra. SHBs are capable of flying long distances, which aids in the dispersal and invasion of new honey bee colonies.

Lifecycle of the Small Hive Beetle

The SHB undergoes a complex lifecycle consisting of four distinct stages: egg, larva, pupa, and adult. Female beetles lay their eggs in clusters, typically in dark and concealed areas within the beehive, such as the edges of frames or in unprotected comb. The eggs hatch within 24 to 48 hours, and the emerging larvae begin to feed on honey, pollen, and bee brood.

The larval stage is the most destructive phase of the SHB lifecycle. As they tunnel through the comb, they deposit a yeast (Kodamaea ohmeri) that causes the honey and pollen to ferment and become slimy. This slime can cause the comb to collapse, and the fermentation process renders the honey unsuitable for bees or human consumption.

After approximately a week of feeding, the larvae leave the hive and burrow into the soil to pupate. The pupal stage lasts for several days to a few weeks, depending on environmental conditions. Once the pupae have matured, they emerge from the soil as adults and begin the reproductive cycle anew.

Damage to Bee Hives

The SHB can cause extensive damage to honey bee colonies. The larval stage is primarily responsible for the destruction, as they feed on and damage the comb, honey, and pollen within the hive. The fermentation caused by the yeast they deposit can also lead to the collapse of the comb and the loss of honey stores.

In addition to the physical damage, the SHB can also impact the overall health and well-being of the colony. The presence of the beetles can stress the bees, leading to a decrease in honey production and an increase in the likelihood of disease and pest infestations.

Identifying a Small Hive Beetle Infestation

Beekeepers should be vigilant in monitoring their colonies for signs of SHB infestations. Some common indicators include:

- Slimed or fermented honey and pollen within the hive

- The presence of small, dark beetles within the hive or on the ground near the hive entrance

- A foul, rotting fruit odor emanating from the hive

- Bees exhibiting signs of stress or agitation

Is this a small hive beetle larvae or a wax moth larvae?

SHB larvae (main image) have three pairs of legs near the head and two large spines projecting from their rear and spines along the length of their bodies. Wax moth larvae (inset) have abdominal legs like a caterpillar (see arrow) and have no body spines.

Treatment and Prevention Protocols

Prevention is crucial when it comes to managing SHB infestations. Beekeepers should focus on maintaining strong and healthy colonies, as they are better able to fend off beetle invasions. This can be achieved through regular hive inspections, proper nutrition, and disease and pest management.

In cases where an infestation has been identified, several treatment options are available. Checkmite (coumaphos) is the only legally registered chemical treatment for SHBs in the United States. However, it should be used judiciously, as it can have negative impacts on bee health and wax quality.

Non-chemical treatment options include beetle traps, such as modified bottom boards or compartmented traps containing a beetle lure. Beekeepers can also utilize physical barriers, such as screens or sticky sheets, to prevent beetles from entering the hive.

- Place hives in partial to full sun.

- Keep soil under hives dry to deter SHB pupation.

- Combine, eliminate, or re-queen weak colonies.

- Clean hives and frames, and maintain in good condition to decrease beetle hiding sites.

- Avoid over-supering hives. Having too many boxes gives beetles excessive space to move, hide, and lay eggs.

- Reduce stresses from other bee pests and diseases.

- Ensure that all colonies sent/received are free of SHB.

- Keep a high ratio of bees to comb to prevent SHB from hiding from patrolling bees. Similarly, take care when splitting hives to have sufficient numbers of bees present in each split.

- If using a non-screen bottom board, regularly remove the accumulating debris to prevent SHB from pupating inside the hive.

- Maintain a clean extraction facility and equipment storage room with humidity levels <50%.

- Process honey within 1-2 days following removal from the colony, clean area thoroughly afterward, and avoid leaving wax cappings and other bee products lying around. If you suspect a SHB infestation, prior to extracting honey, freeze honeycomb at 10°F (-12°C) for at least 12 hours to kill beetle life stages.

- Avoid using grease patties for mite control or adding protein patties for spring buildup. These are attractive to SHB and may increase chances of infestation.

Biological controls, such as nematodes and Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt), have also shown promise in managing SHB populations. However, their efficacy can vary, and beekeepers should experiment with different methods to determine the best approach for their specific situation.