r/Beekeeping Wiki

Why Are My Bees Dead/Missing?

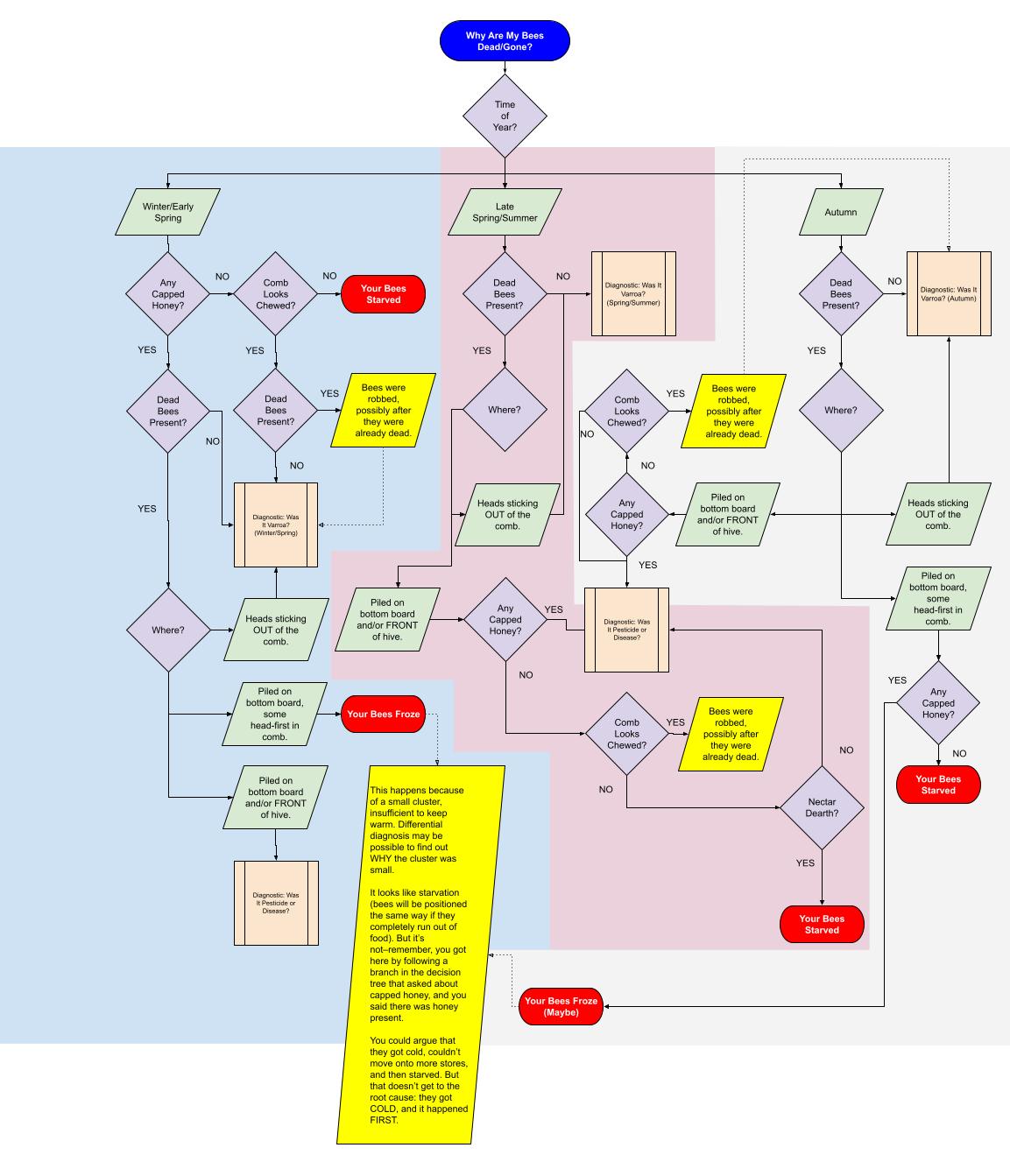

It happens to every beekeeper sooner or later: one or more colonies of your bees has died, and you’re left to pick up the pieces. Why did they die? What if it was something you did (or didn’t do)? If you don’t know, you can’t prevent it from happening again. Below is a flow chart or decision tree that may be helpful for diagnostic purposes, especially if you’re a relatively new beekeeper.

NOTE: This is NOT an exhaustive guide to diagnostics. It’s a very basic decision-making tool that is designed to help relatively inexperienced beekeepers perform a triage. It isn’t going to lead you down to an exotic conclusion like, “You have buckeyed bees,” or “Your bees are being eaten by Asian giant hornets.” Those are real failure modes, but they are only likely in very specific geographic locales where the etiologic agent for them even exists. We’re looking for common stuff first, and trying to rule out what doesn’t fit.

Always remember this adage: “When you hear hoofbeats, think horses. Not zebras.”

The Chart

Process Documents

The orange boxes on the flow chart above are discrete procedures that you can use to try to make a differential diagnosis between modes of colony failure. Here are links to the pages dedicated to those procedures.

Not Seasonal

Pesticides and Diseases

Pesticide kills can happen anytime the weather is warm enough for bees to forage, or anytime pesticides are being applied in circumstances that might lead them to drift into an apiary. If you live someplace that is reliably too cold for bees to fly or for agricultural chemicals to be sprayed during the winter, you’re extremely unlikely to see pesticide kills during the months of winter. Your bees are stuck at home.

Disease can happen anytime, although certain kinds of disease certainly are more prevalent at different times of year.

This document is geared toward ruling out common diseases, and also differentiating them from pesticide kills.

Note that in addition to the diagnostics discussed in this process, the differential diagnostic processes involving varroa often involve distinguishing varroa-related symptoms from the symptoms of unrelated disease.

- Diagnostic: Was it Pesticide or Disease?

Robbery

Robbing behavior is when one colony of bees is attacked by another colony of bees. It can happen at any time of year, provided that three preconditions are met:

- The ambient temperature is above 10° C (50° F).

- The victim colony smells like food.

- The victim colony is not strong enough to repel foreign bees at its entrance.

If it is warm enough for sustained flight, colonies will send out foragers to scout for food, no matter the time of year. If there is nothing in bloom, there is no forage to be found—but that will not stop the colony from trying to find some, even if it already has plenty of stored food. Foragers will be attracted to anything that smells like a food source.

If the food source is another colony of bees, then most of the time wandering foragers find the other colony, but the other colony’s guards repel them. They don’t get a food reward, so they move on.

Weak colonies do not have the strength to fend off these marauding bees; they gain entry to the hive, eat some honey, and then go home to do the waggle dance, recruiting their sisters.

Before long, you have bedlam in and around the victim colony.

Winter/Early Spring

Varroa can kill colonies at any time of the year, but it is least likely to be the culprit (at least directly) during the months of winter and the very early part of spring. In many parts of the world, winter conditions are sufficiently harsh as to lead to a cessation of brooding activity; without brood, varroa are unable to reproduce. And concomitantly, winter and early spring are the part of the year in which honey bee colonies are most at risk of starvation—the longer the winter, the more likely that they will have burned through their food stores.

So it’s important not to jump to conclusions and say, “Okay, let’s assume it’s varroa unless we can prove otherwise”; if your bees are going to die of something that doesn’t involve V. destructor, this is the time of year that it is most likely to happen. As you traverse the flow chart above for a winter or early spring deadout, you’ll be asked to assess food stores and look at the arrangement of any dead bees inside the hive before you start looking for evidence of varroa.

- Diagnostic: Was It Varroa? (Winter/Early Spring)

A Note About Frozen Bees, Starvation, Moisture Problems and Excess Space

Bees are really good at dealing with cold weather, provided that they are healthy and have plenty of carbohydrates for calories, they’re dry, and they’re sheltered from wind. It is also very helpful for them to be housed in a hive that is appropriately sized for the population of bees residing in it, and there is a growing body of evidence that indicates that, all else being equal, colonies that are inside an insulated hive are going to do better than colonies that are in an uninsulated hive.

But if a colony is starving, wet, exposed to cold wind, or in a hive that’s too big for the population inside of it, it won’t do well.

Telling the difference is not always straightforward. A colony that died while it had food stores present did not starve. Some people lump deaths by starvation together with deaths from exposure to cold. The symptoms visible post-mortem (other than presence or absence of food) are really similar, so this is understandable. But the cause-and-effect relationship that leads to death is quite different.

When a colony dies of starvation or of exposure to excessive cold, you’ll find a heap of dead bees on the bottom board. Often, there will be bees still lodged head-first in the comb whereever the clustered colony had been before it ran out of food. These bees did not die while they were looking for food. That’s a misconception. They were “heater” bees. In cold weather, bees inside of the cluster rapidly vibrate their flight muscles—they shiver, basicaly—to generate heat that will warm the cluster. By getting into the comb, these heater bees allow the cluster to be more compact, making it easier to keep warm.

If a colony died of starvation, then there will be no honey anywhere in the hive. The bees ate it all, burned all the calories it had to offer them, and then, lacking calories, they got cold and died.

If a colony died of exposure to cold, the bees will be chilled until their body temperatures fall below 10° C (50° F). At this temperature, they enter a state of torpor, and become unable to move. Because they are unable to move, they cannot move onto new food stores. Because they cannot move onto new food stores, they stop metabolizing carbohydrates, and they die.

The cause/effect relationship is reversed.

What makes bees get cold?

- The cluster is too small (many causes are possible, but varroa is the most common, especially among hobbyist beekeepers; a poor queen or a disruption to brooding activity in late summer/early autumn are also strong possibilities).

- The hive is too big (this is usually almost the same thing as the cluster being too small).

- They get wet.

- They are exposed to drafts.

- The hive is not adequately insulated. There are several different strategies for dealing with these issues, but most of them are outside of the scope of a basic diagnostics guide. We’re getting into the minutiae of hive configuration if we talk about them in detail, and that’s not really the point of this document.

Late Spring/Summer

When you find a dead hive in the late spring and summer months, you

- Diagnostic: Was It Varroa? (Spring/Summer)

Autumn

- Diagnostic: Was It Varroa? (Autumn)

Other Notes

This diagram is not a comprehensive listing of every possible failure mode a colony of bees can experience. It’s a guide to help you zero in on likely causes, so that you can drill down to figure out whether they are a good fit for what you see in your dead hive. There are lots of ways that a colony can die that aren’t covered here because they’re obvious as soon as you see them, or very rare, or just hard to distinguish.